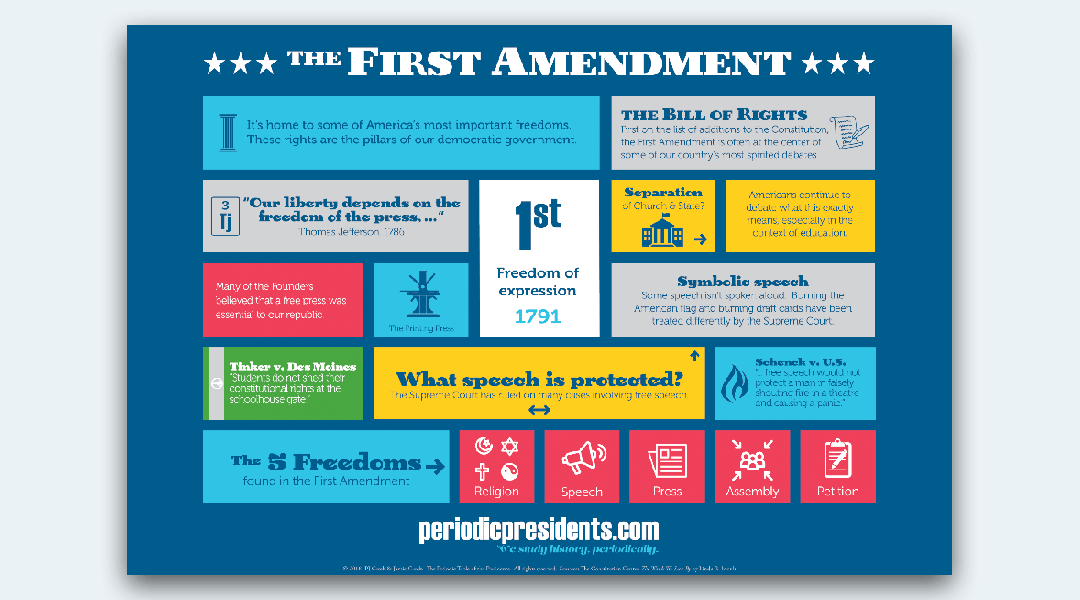

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects what are commonly known as The Five Freedoms: freedom of religion, freedom of press, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of petition. The amendment is part of ten amendments to the Constitution known as the Bill of Rights, which was adopted in 1791. The First Amendment Reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” (Source: National Archives)

This amendment gives Americans the right to express themselves verbally and through publication without government interference. It also prevents the government from establishing a “state” religion, and from favoring one religion over others. And finally, it protects Americans’ rights to gather in groups for social, economic, political, or religious purposes; sign petitions; and even file a lawsuit against the government. (Source: History.com)

Freedom of the press and freedom of speech are closely related, and are often the subject of court cases and popular news. Understanding how and when these rights are protected by the First Amendment can help us better understand current events and court decisions.

While the First Amendment acknowledges and protects these rights, there are limitations to how the amendment can be invoked. For instance: people are free to express themselves through publication; however, false or defamatory statements (called libel) are not protected under the First Amendment.

What is Defamation?

Defamation occurs if you make a false statement of fact about someone else that harms that person’s reputation. Such speech is not protected by the First Amendment and could result in criminal and civil liability. Defamation is limited in multiple respects though.

If you make a false statement of fact about a public official or a public figure, more First Amendment protection applies to ensure that people are not afraid to talk about public issues. According to New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), defamation against public officials or public figures also requires that the party making the statement used “actual malice,” meaning the false statement was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

Parodies and satire are protected by the First Amendment (and are not defamatory). Parodies and satire are meant to humorously poke fun at someone or something, not report believable facts.

The First Amendment also specifically refers to the interference of government in these rights. This ensures that Americans are free to critique the government, but it does not give Americans blanket immunity to say whatever they want, wherever they want, without consequences. Lata Nott, Executive Director of the First Amendment Center, explains:

The First Amendment only protects your speech from government censorship. It applies to federal, state, and local government actors. This is a broad category that includes not only lawmakers and elected officials, but also public schools and universities, courts, and police officers. It does not include private citizens, businesses, and organizations. This means that:

The U.S. Supreme Court has often been called upon to determine what types of speech are protected under the First Amendment. Since the adoption of the Bill of Rights, hundreds of cases have been seen by the Supreme Court, setting precedence for future cases and refining the definition of speech protected by the First Amendment.

Cox v. New Hampshire

Protests and freedom to assemble

Elonis v. U.S.

Facebook and free speech

Engel v. Vitale

Prayer in schools and freedom of religion

Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier

Student newspapers and free speech

Morse v. Frederick

School-sponsored events and free speech

Snyder v. Phelps

Public concerns, private matters, and free speech

Texas v. Johnson

Flag burning and free speech

So what types of speech are protected by the First Amendment? Let’s turn to some experts to better understand:

Censorship is the suppression or prohibition of words, images, or ideas that are considered offensive, obscene, politically unacceptable, or a threat to security (Sources: Lexico and ACLU). The First Amendment Encyclopedia notes that “censors seek to limit freedom of thought and expression by restricting spoken words, printed matter, symbolic messages, freedom of association, books, art, music, movies, television programs, and internet sites” (Source: The First Amendment Encyclopedia).

Censorship by the government is unconstitutional. When the government engages in censorship, it goes against the First Amendment rights discussed above. However, there are still examples of government censorship in our history (see the 1873 Comstock Law and the 1996 Communications Decency Act), and the Supreme Court is often called upon to ensure that First Amendment rights are being protected.

Private individuals and groups still often engage in censorship. As long as government entities are not involved, this type of censorship technically presents no First Amendment implications. Many of us are familiar with the censoring of popular music, movies, and art to exclude words or images that are considered “vulgar” or “obscene.” While many of these forms of censorship are technically legal, private groups like the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) work to make sure that the right to free speech is honored.

To learn more about the history of censorship in the United States, and across the world, consider the sources below.

The widespread use of the internet, and particularly social media platforms, has presented new challenges in defining what types speech are protected by the First Amendment. Social Media platforms are private companies, and we learned above that private companies are legally able to establish regulations and guidelines within their communities–including censorship of content or banning of members.

Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, states that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” That legal phrase shields companies that can host trillions of messages from being sued into oblivion by anyone who feels wronged by something someone else has posted — whether their complaint is legitimate or not.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have argued, for different reasons, that Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms have abused that protection and should lose their immunity — or at least have to earn it by satisfying requirements set by the government.

Section 230 also allows social platforms to moderate their services by removing posts that, for instance, are obscene or violate the services’ own standards, so long as they are acting in “good faith.” (Source: The Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University)

But what happens when politicians use these platforms to communicate with the people they lead? Is it legal for a social media platform to ban a person from using their service? If a politician bans or blocks members from interacting with their content on a social media platform, is it considered a First Amendment violation?

Below are some additional sources discussing how the First Amendment applies to online interactions and social media:

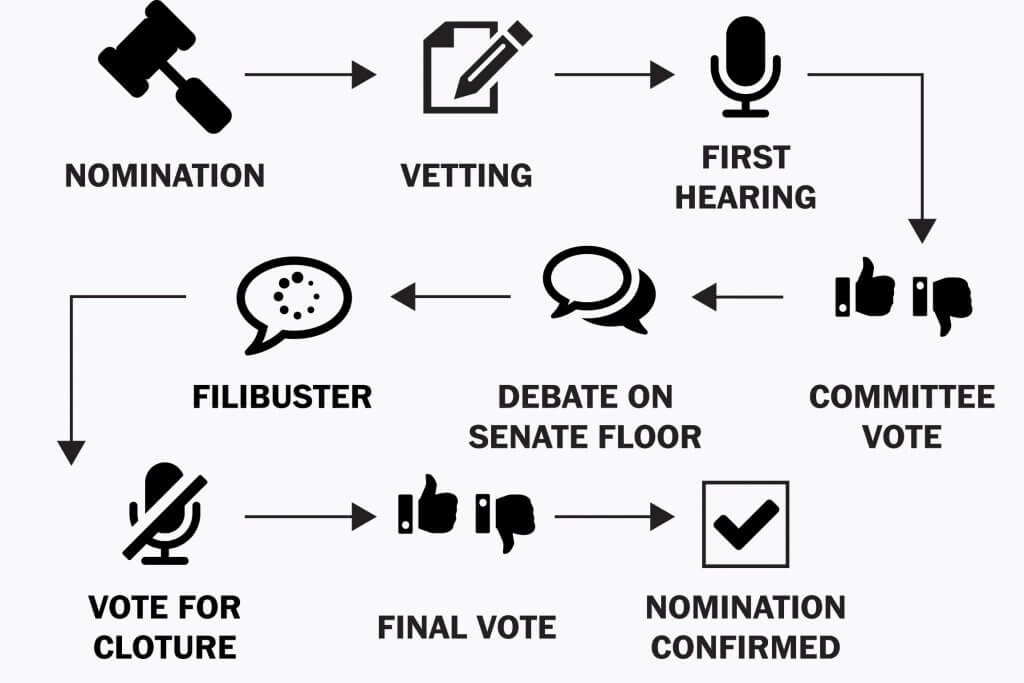

Array ( [acf_fc_layout] => page_related_post [post] => WP_Post Object ( [ID] => 324833 [post_author] => 328 [post_date] => 2020-09-21 13:18:13 [post_date_gmt] => 2020-09-21 17:18:13 [post_content] => The passing of Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg on September 18, 2020 has created a vacancy in the 9-seat Supreme Court. There is no recent precedent for a confirmation vote so close to a presidential election. Nomination and confirmation of a new member of the Court involves both the President and the Senate. About the President: Donald J. Trump, Republican, was elected the 45 th President of the United States in November 2016. (Source: Whitehouse.gov) About the Senate: The 116th Congress (whose 6-year terms last from 2019-2021) is comprised of the Majority Party: Republican (53 seats) and Minority Party: Democrat (45 seats). Other Parties include: 2 Independents (both caucus with the Democrats), for a total of 100 seats. (Source: Senate.gov) “The Constitution states that Justices ‘shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour.’ This means that the Justices hold office as long as they choose and can only be removed from office by impeachment.” A Supreme Court Justice may serve for life. While this position has typically gone to lawyers and judges, “the Constitution does not specify qualifications for Justices such as age, education, profession, or native-born citizenship. A Justice does not have to be a lawyer or a law school graduate, but all Justices have been trained in the law.” (Source: Supremecourt.gov) Below is the workflow for nominating and confirming a Supreme Court Justice: [caption align="alignnone" width="739"] Everything you need to know about appointing a Supreme Court justice (The Washington Post)[/caption] About the Supreme Court: The Supreme Court interprets the Constitution to upload the rule of law. In short, it makes the decision on what is or is not legal by hearing arguments on both sides of the issue, studying past applications of the law, as well as the Constitution. The decisions of the Supreme Court have an important impact on society at large, not just on lawyers and judges. The decisions of the Court have a profound impact on high school students. In fact, several landmark cases decided by the Court have involved students, e.g., Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969) held that students could not be punished for wearing black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. In the Tinker case, the Court held that "students do not shed their rights at the schoolhouse gate." (Source: USCourts.gov) It is common knowledge, and often heard in movies and on television, that when a person is arrested they should be told that they “have the right to remain silent”. This is because of Miranda v. Arizona (1966) for which the Court ruled that those in police custody must be informed of their rights. Some additional examples of how Supreme Court rulings affect our everyday lives include:

Everything you need to know about appointing a Supreme Court justice (The Washington Post)[/caption] About the Supreme Court: The Supreme Court interprets the Constitution to upload the rule of law. In short, it makes the decision on what is or is not legal by hearing arguments on both sides of the issue, studying past applications of the law, as well as the Constitution. The decisions of the Supreme Court have an important impact on society at large, not just on lawyers and judges. The decisions of the Court have a profound impact on high school students. In fact, several landmark cases decided by the Court have involved students, e.g., Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969) held that students could not be punished for wearing black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War. In the Tinker case, the Court held that "students do not shed their rights at the schoolhouse gate." (Source: USCourts.gov) It is common knowledge, and often heard in movies and on television, that when a person is arrested they should be told that they “have the right to remain silent”. This is because of Miranda v. Arizona (1966) for which the Court ruled that those in police custody must be informed of their rights. Some additional examples of how Supreme Court rulings affect our everyday lives include:

^Click the image above to access the PA voter registration page[/caption]

^Click the image above to access the PA voter registration page[/caption]

American Civil Liberties Union The ACLU has been a defender of individual rights for one hundred years and provide s numerous downloadable “Know Your Rights” guides. First Amendment Center – Freedom Forum Institute The Freedom Forum raises awareness of First Amendment rights through education and advocacy and works to facilitate relationships between the media and the public. Their website includes an in-depth protest primer that includes interactive examples. Movement for Black Lives M4BL provides resources for protesters including tactics to stay safe, assess risks, and guard against infiltration and misinformation. They also provide a list, subdivided by state, county, and city, of “Verified Bail Funds.” National Lawyers Guild Since 1937, this association’s mission has been to serve the people “by valuing human rights and the rights of ecosystems over property interests.” The Guild defends the First Amendment rights of protesters through their Mass Defense and Legal Observer programs . Protect the Protest An initiative through several nonprofit organizations to “defend dissent” and shield “activists, community organizers, journalists, and small media organizations” from SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation). Protect the Protest can help connect protesters to legal representation and financial aid.